I was in the pub a few months ago with a good friend of mine when we first mentioned The Skew.

We were having a few pints on a sunny evening after work and generally discussing life when they mentioned about how doubts about their relationship were taking up a lot more of their thoughts than they otherwise should have been, even intruding into moments when there wasn’t any reason to devote brain space to that issue.

I’m a firm believer that traits that we traditionally associate with mental illness, (paranoia, hallucinations, or in this case, intrusive thoughts) are much more common than the public consciousness would have itself believe. It was a little weird to see a friend of mine, who had always seemed neurotypical, describing my abnormal thought processes exactly in their own thoughts. I’ve said before that our mental illnesses are selfish, and that definitely applies here. I like to think of my nice healthy brain as a bell curve:

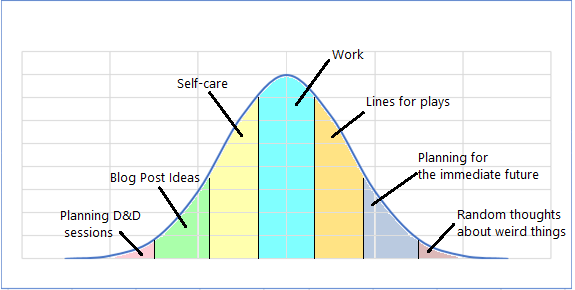

The y axis is how much of my brain space I have to devote to thinking about things, while the x axis shows how much time I should normally spend thinking about certain things. The area under the graph is the amount of brain space you have to think about things for the day, and can be divided into little parcels of thought on different themes. This is how my brain should work an any given day, divided into nice, responsible, manageable chunks.

In the middle we have things like work, concentrating for eight hours a day on fairly complex systems. Off to the sides we find things like learning lines for shows, or thinking about relationships, needing a fair amount of brain power. A little further on, we find remembering to eat and shower and sleep, activites that actually take up very little conscious thought. Then, at the very extreme edges, there lie all of the inconsequential tiny offhand thoughts that occupy your mind during a day: “Ooh, look, a bird.” ”I wonder where that guy is going?” “Was she looking at you?”

Of course, this is my brain in a perfect world, cleanly defined and delineated. Realistically, during those eight of hours of work, my brain will often drift sideways into thinking about what I’m having for dinner, what the next line of that song is, or how the pattern in the carpet looks. On the other hand, when I’m in the shower or cooking, my mind will sometimes wander to work thoughts. On average, my brain ends up looking like a bell curve, if a slightly lumpy one.

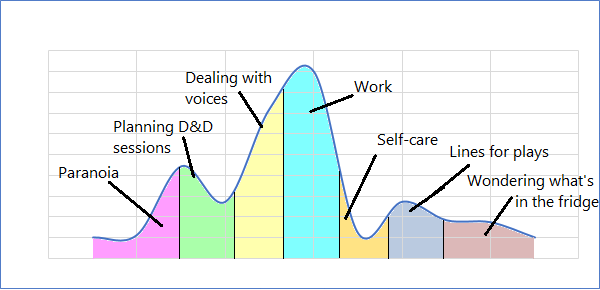

Voice-hearers, of course, will recognise that those last few tiny thoughts are the ones most likely to spiral into obsessions; “Was she looking at you?” can very quickly turn into “They’re all staring at you.”

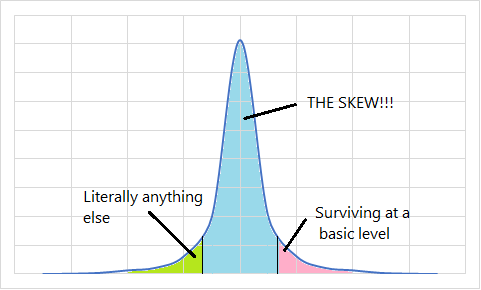

The point where disruption to your life occurs, whether as a result of mental illness or not, is where we find…

THE SKEW

The skew is where one thought tips the graph of your mind like so:

But as high school maths will tell you, the area under the curve stays the same. Just because you increase the concentration of thoughts about one subject, that doesn’t mean you get more space to think; your bucket of thought for the day won’t get any bigger. In fact, every increase in one area will directly take away from another. With schizophrenia, this can manifest in less attention being given to things like personal hygiene or dressing properly, both very common symptoms, but even in neurotypical people, a single thought can overtake you and make you obsess to the detriment of all else.

If you’ve ever had someone break up with you, you’ll know something of this; you spend a few days not being able to think of much else, whether cursing them or wishing they’d take you back. Your perception is skewed towards one thought, and that thought takes up space outside of its normal boundaries.

Psychosis, especially in the form of voices, can skew thoughts towards any part of the axis; indeed, one of the scariest things about hearing voices can be when your voices focus on a seemingly random element of thought. This can even make you believe that the thoughts you have have meaning beyond their own, leading to false assumptions about their content: delusions.

It’s important to know that The Skew can make a problem seem insurmountable: a problem you spend all day contemplating is surely a problem worth spending a day on, right? But just as worrying about your Skew doesn’t make the rest of the things that need your attention less important, that one occupying thought isn’t unassailable. Often times the best way to deal with a Skew is to… just… wait. Remember your first breakup? I’d bet you’re a lot less broken up about that now, (pun intended).

Don’t sweat the Skew. Worrying about it is normal, even healthy. But don’t let yourself obsess. Sharing your problems with other people puts them into perspective as something that is surmountable and able to be talked about. Even something as simple as leaving the room for a change of scenery can shift your brain out of its rut. Fixating on a problem lets it fester and grow out of proportion, making it seem bigger than it possibly can be.

And Skews don’t have to be bad: falling in love provides one of the biggest Skews of all, as anyone who has ever had a friend with a new relationship will irritatedly confirm. Just remember not to devote too much of your thought bucket to any one thing and you’ll be fine.

And if this rambling tale of buckets, graphs and frankly amateur psychology leaves you cold, then you’re probably thinking: “Wow… this guy’s got a Skew loose.”

J x