A while ago, I was asked to write something for people who, unlike me, are just having their first experience of psychosis. I’ve thought about what to say for a long time, and I’ve come to the conclusion that I can’t talk to you about what you’ll experience; from talking to a lot of good friends I’ve made throughout my illness, everyone’s experience is so different I just don’t think that will be useful. What I do know, is how much I wish I’d had someone to tell me right at the start that this wasn’t the end of my life, and despite all the awful things that I would experience, it didn’t mean that I wouldn’t be happy again.

With that in mind, the rest of this is addressed to Joe, at 7:30pm on the 3rd of October 2014.

Hey buddy! How are you doing? I know you’re scared, but it’s going to be ok, I promise. About an hour ago, you were walking back from the shop, when you heard your grandad’s voice for the first time in years. He told you to kill yourself. You can feel his words burning in your mind, replying over and over. It doesn’t mean that he can still hurt you.

An hour from now, you’ll walk for four miles trying to convince yourself this isn’t happening, you can’t be crazy. You’ll fight with yourself over whether to tell anyone about this, and you’ll go and find a friend and walk three miles more. By the time you get home you’ll be exhausted, but you can’t sleep because if you do you know something terrible will happen that you won’t be able to prevent. You won’t tell your friends or anyone else about it for two weeks because you’re scared that they’ll call you a freak. A monster. They won’t. You are not a monster.

When you finally do get the courage to talk to someone, things will happen pretty fast. You’ll see a lot of doctors, eight if I remember correctly, in the next three weeks, and you’ll go to some scary, alien places where people will say a lot of long words that just wash past you as you try to control the visions of the fire on the floor and the stab wounds in their chests. It doesn’t mean that any of that is real.

In a month’s time you will have the worst day of your life. You’ll be sitting in the university library, trying desperately to claw the fog from your head enough to salvage your failing degree when the whispers will start up behind you, just underneath your shoulderblades. You’ll text a friend, asking if you can stay there tonight. You’ll make a big mistake: instead of waiting five minutes for the bus, you’ll decide to walk for close to an hour, as the voices overtake you completely. You will arrive at your friends’ house and stab them both to death with a kitchen knife. You’ll see the terrible wounds in their chests and arms, feel their blood on your skin, and smell the stench of iron in the air. You’ll wake up weeping in the middle of a road and run back there, hoping you can save them. Your world will collapse when they open the door, completely fine and very worried. You’ll still see their bodies and smell their blood in your nightmares three years from now. It doesn’t make you a killer.

Your doctor will recommend you start taking medication. The first three days are a comfortable cloud of anaesthesia; you won’t remember if you could hear voices or not, but if you did, you didn’t care. You’ll take a lot of different medications over the next three years, all of them having side effects that leave a bitter aftertaste, and none of them doing anything but muffling the voices. At one point you will be so poor you realise you’ll have to choose between food and medication. You pick the third option, even though the voices tell you not to, and ask a friend for help. I’m proud of you for that.

You’ll tell the rest of your friends about it, and they won’t give a damn. They love you, just as much as you love them, and a tiny quiet part of you will know that you’d feel the same way if they told you all this. They will save your life, because you trusted them.

After a waiting list that was far too long, you’ll start group therapy, and meet a group of people just like you. You didn’t think there were any. At one point your grandfather screams at you so loudly you’ll jump in your seat, and you’ll have the unique and surreal experience of having a group of schizophrenics look at you like you’re crazy. They are some of the best and strongest people you will ever meet, and you will be proud to call them friends.

It will get better from there. You’ll get a part time job to help pay your way through university. You’ll quit after six months because two hours of extra work a week feels like it’s going to tear your mind apart. But soon you’ll get a full time job, and work forty hours a week, and smile every time he says that you’re going to quit. You’ll tell him to go fuck himself a whole lot.

You’ll even fall in love again. You look at her and just for a moment the thunderclouds over your soul part and it will seem like the whole world is made of golden light. You’ll be drunk at a party in two months time and he’ll make you watch her die for eight hours on a TV screen that floats above your head. He laughs gleefully the whole time, drinking in the torture he is inflicting on you. After that, it burns you to even look at her, and you shut off your feelings when she’s around. But you move on, and you fall in love again. A lot. Perhaps too much. But fighting to be able to feel for other people makes you feel better. Gradually, you’ll begin to feel better about life in general, more positive about the future. It doesn’t mean that you won’t wake up covered in blood to find your ex in your bed with her throat slashed, or feel yourself being crucified, or feel rats eating their way out of you. or anything else he can think up. But it does make it hurt a little less each time.

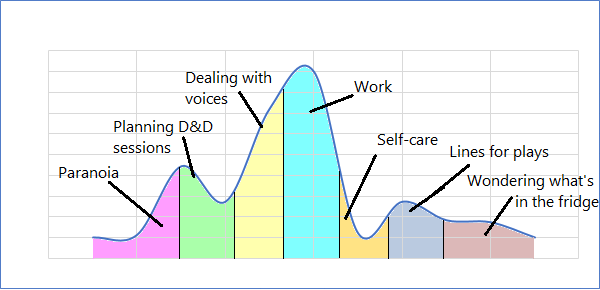

One day you decide you’ll forgive him. He won’t scream, or shout, or resist. You find that when you listen to him, try to understand his concerns and decode what he is showing you, he’ll appear a lot less. You’ll begin to understand that your voices are just another part of your brain, trying to keep you safe and alive just like the rest of it. It doesn’t happen overnight, but you find the strength within yourself each time to thank the voices for their concern, and tell them that you are all safe, that they have nothing to worry about. Do that for long enough, and the voices will retreat back inside your head, until they become almost tame. You’ll still have your danger days, but it will feel like just a part of everyday life. You’ll just be… fine. You can’t remember what life was like before this, but then you can’t really remember the worst days either. You’ll graduate, get a full time job, date a bit, play a crap ton of D&D and finally decide you want to write about your experiences so other people don’t feel like you did back at the beginning.

If you are just experiencing psychosis for the first time, please remember this. You are not alone. You are not a monster or a freak, and you are loved, more than it feels possible right now. You do have the strength to seek help, to trust people, and to persevere even when you can’t or don’t want to see it through. I’m not going to tell you that it will be easy, or that you won’t have to fight tooth and nail for every shred of happiness and positivity. But I believe in you. Because I didn’t believe in me.

Joseph Hand is a biology graduate, IT specialist and aspiring actor from Southampton, UK. He is an avid tabletop gamer and singer, and is quite partial to the music of Johnny Cash.

His recorded work has been used by the NHS to introduce recently diagnosed psychosis sufferers to alternative therapies, such as roleplaying gaming.